Early drafts of the EU’s Regulation on Deforestation-Free Products did not include rubber. In fact, later drafts didn’t either. This in spite of a 2018 Fern briefing that estimated 3m hectares of forest had been lost since 2000 and the fact that the EU remains the destination for 25% of the rubber produced globally.

Now the Regulation has arrived in its all-but-final state. While some have raised eyebrows at the exclusion of peatland, savannah and coconuts, rubber products that are associated with deforestation will most definitely be denied market access in the EU. Companies trading rubber and rubber-based products on the EU market will need to change their business processes to comply with the Regulation.

Rubber Under the Radar?

According to Fern’s briefing, as of 2018 there weren’t any estimates available for rubber’s contribution to illegal deforestation. This could tell us one of two things, either rubber concessions only exist in areas that have been cleared legally or that rubber’s the odd commodity out in global attempts to monitor and mitigate illegal deforestation…

…Until now.

The eye of Satelligence has been focused on Indonesian agriculture for a while; their assistance on palm oil’s sustainability journey is well documented. Their data shows that the palm sector has been setting standards that other commodities ought to live up to. Now, Satelligence is showing off the range of commodities the platform can monitor to help the rubber industry do the same. They’ve been working with a number of key sectoral players, including sustainable investment firm &Green, to end encroachment on protected areas from rubber plantations.

How the Industry Regulated Itself

It isn’t just Satelligence who have taken an interest in deforestation in the industry, changes that originate within the industry have shown that rubber companies are taking responsibility for what goes on in their supply chains. Fern’s rubber briefing coincided with the creation of the Global Platform for Sustainable Natural Rubber (GPSNR), a group dedicated to sustainable, equitable, and fair rubber supply chains that includes rubber giants like Michelin and BMW. As a declaration of private rubber’s commitment to trust, transparency, and shared responsibility, the organisation’s establishment was an important milestone for the industry.

In an open letter to the European Commission, key players in the industry said that, should rubber be excluded from the regulation, “hundreds of vulnerable groups will be pushed further into poverty, and forests toward greater destruction.” Granted, these concerns weren’t shared industry-wide. Some companies lobbied their socks off to ensure rubber was left off the bill.

NGOs are counting the inclusion of rubber on the regulation as a victory, as will those in the industry who believe that traceability = equality. For the open letter signees, it will level the playing field for companies who’ve nothing to hide in their supply chains.

Preparing for the EU Deforestation Regulation

Satelligence’s data can help companies committed to supply chain traceability comply with the EU regulation in several ways. First, companies can pinpoint the locations of their concessions using Satelligence’s database of ancillary concession information. No small feat among thousands of rubber smallholders. They’ll also be able to clarify whether the rubber they source is the result of deforestation clearing, proving their products are deforestation free, or allowing them to make the appropriate changes to the sourcing decisions. An alert and an AI-powered deforestation hotspot detection system will equip them with the tools to capture deforestation risks before they occur.

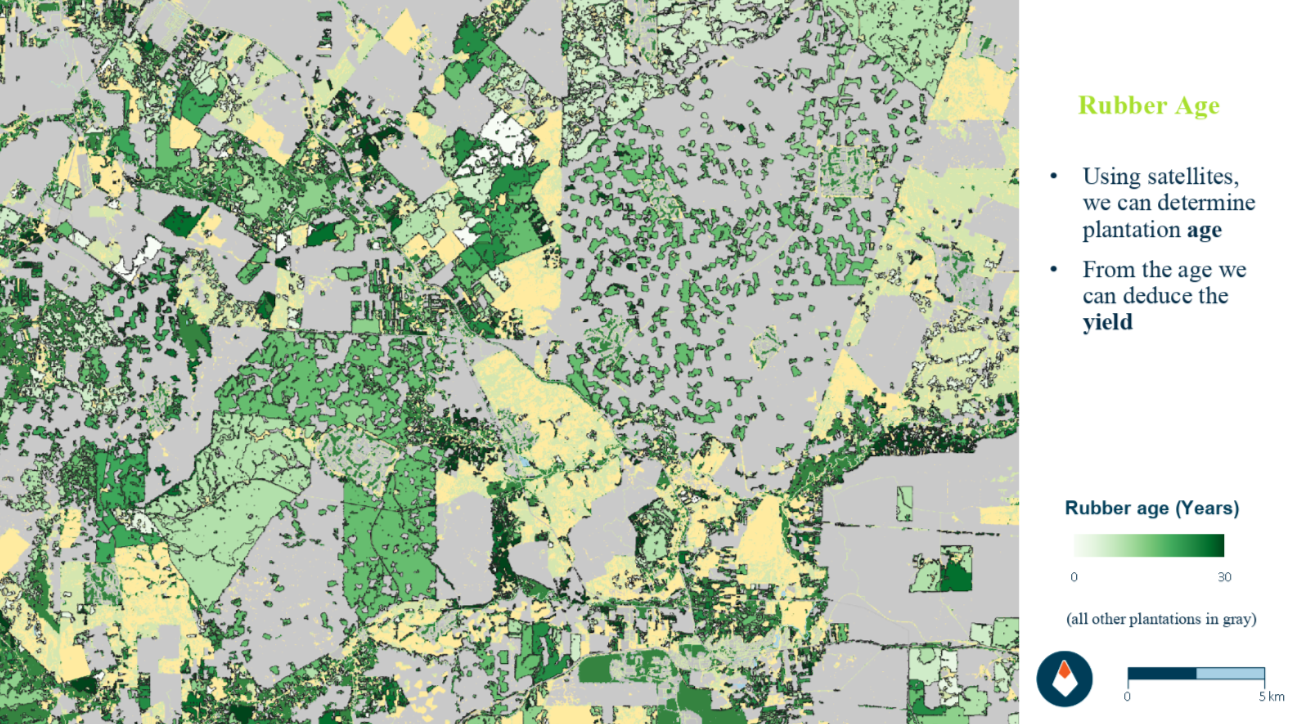

Satelligence can also provide data on the age of rubber plants, so farmers know which areas need replanting. A lot of new land is cleared to replace non-productive trees that are more than 20-25 years old. With Satellite data, companies can keep tabs on the age of their plants and allocate resources to replanting initiatives, obviating the need to clear more land.

If we’re to learn anything from the rubber industry’s environmental performance over the last 15 years, it’s that private pressure can be used to further the public good. The efforts of private companies like the signatories of the open letter to the European Commission, Satelligence, and their clients have brought rubber supply chains out of the dark and into a more transparent, trustworthy light. In recognising the business opportunities inherent in effective regulation of supply chains and sustainable best practice, the rubber industry has shown how reform needn’t be an obstacle to good business, it can drive it too.